Episode

June 30, 2020

Should the United States Mandate Paid Family Leave? (29:27)

As families try to balance work and childcare, a popular answer is to have government mandate paid family leave. Will mandating paid leave help families or could a law hurt the very workers it is meant to help? Veronique de Rugy, senior research fellow at the Mercatus Center and adjunct scholar at the Cato Institute; Rachel Greszler, research fellow at the Heritage Foundation; and Camille Busette, director and senior fellow at the Brookings Institution will discuss in this episode: should the United States mandate paid family leave?

Transcript

Bret Baier: A battle may be brewing within the Republican Party over paid family leave. President Trump…

Caleb O. Brown: As families try to balance work and childcare, a popular answer is to have government mandate paid family leave. Will mandating paid leave help families? Or could a law hurt the very workers it is meant to help?

President Trump at the 2020 State of the Union Address: I am also proud to be the first president to include in my budget a plan for nationwide paid family leave…

Mika Brzezinsky, MSNBC: Let’s start off with asking you what you have against paid family leave, at this point, since you seem to be against it?

Rep. Raúl Labrador (R-ID): Well, I just don’t think it’s the government’s role to give businesses more, more things to do and to pay for…

Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT): What kind of society are we when we tell a woman she cannot love and nurse and be with her baby?

Caleb O. Brown: If Americans can agree on nothing else, we should be able to agree that the tone driving our political discourse is unhealthy for our country. In order to debate contentious public policy issues without abandoning deeply held principles, the Cato Institute and the Brookings Institution have introduced Sphere. In this episode: Should the United States mandate paid family leave? All right, the question before us today: Should the government mandate paid family leave? And our guests today are Veronique de Rugy, senior research fellow with the Mercatus Center and adjunct scholar at the Cato Institute, Camille Busette, senior fellow and director of Race, Prosperity and Inclusion Initiative at the Brookings Institution, and Rachel Greszler, a research fellow at The Heritage Foundation. Camille, I would like to start with you. What are the upsides of paid time off for parents when a new child is born? And, you know, why should that be mandated?

Camille Busette: Well, thanks very much for the question, Caleb. I’m actually of the opinion that one of the things we want to solve for as we move forward to 2050 and beyond in the U.S. is how do we continue to keep a really rapid pace of economic growth while at the same time trying to lessen the kind of fiscal drag that we have on – that healthcare places on our GDP? And so, for those reasons, I actually think that paid family leave is actually really important. It’s important for a number of reasons. Research that’s been done on the California and New Jersey plans shows that paid family leave does increase labor force participation, particularly for women. So, that’s a good thing. That’s helpful because when we get increased labor force participation, we also get increased money that people can spend. And that’s helpful for the economic growth. There also have been a number of benefits shown for children, for their developmental, making developmental milestones, and also for increase in parent-child bonding, which, of course, is very important for a range of positive outcomes for kids.

Caleb O. Brown: All right, so Rachel, to you. You are relatively less supportive of mandating paid family leave. Why is that?

Rachel Greszler: Well, I think that if we mandate paid family leave in the U.S., we’re gonna end up with a lot of unintended consequences that we didn’t want to happen. And you’re gonna end up with some discrimination in hiring, particularly against women of childbearing age and others who are more likely to take leave. And we’ve also seen some consequences like lower earnings, higher unemployment rates, and fewer promotions for women when you have these types of policies. And so, I think we all want people to be able to take paid family leave, we absolutely support that and families are the foundation of society. But the question becomes do we mandate it and have these consequences? Do we have a government program to try and fit the needs that have not yet been met by the private sector in there, too? I don’t see how a one-size-fits-all, a bureaucratic and rigid program could meet the needs the way that an individual, when they sit down with their employer, can work out a flexible and accommodating policy that really will get to those needs in a better way. And so, you end up having programs that don’t really benefit the people you’re trying to reach. There are a lot of people that don’t use the government programs, particularly the lower-income ones. And that’s one of my biggest fears, is that we’ve seen across countries and even within some of the U.S. states is, that they’re redistributing resources away from the lower-income people that we are really trying to help, and the benefits are all going to middle and upper-income earner families. And so, to me, that says, let’s not look to the government to provide paid leave, but maybe look to the government at ways that they can help make the resources be available for more workers and employers to work these policies out.

Caleb O. Brown: Okay, and Veronique, nobody is really questioning the value of paid family leave. You see a lot of costs with a mandate.

Veronique de Rugy: Well, so, I mean, I agree with you, Camille, that paid leave, and Rachel just said it, I mean, is a great benefit. There is no doubt, and in fact, this is why the private sector has actually been providing it a fair amount, in different forms, and increasingly, and in fact, since the sixties, it’s increased. The prior provision of paid leave in one form or another has increased by 280%, which is not insignificant. And there’s, as you said, like there’s a lot of evidence about the child, about parents, children bonding. There’s a lot – there are a lot of benefits for the mother and for their children that is well-established. The problem about the way we talk about the benefit, is if we only talk about the benefit without talking about the cost. And Rachel has hinted to a lot of these costs, and they’re not insignificant either. And the problem, also with them, is as very, as it is often the case, they end up hurting the people we actually are trying to help. Less so the higher-income earners or workers. But, more so, really, the people who would who need it the most. The people who actually don’t have it right now end up being the one penalized. And I think the federal government is absolutely the wrong actor to try to address this need. And we need to figure out better ways to offer flexibility for workers and employers to be able to work things out.

Camille Busette: You know, I think that’s great. Let’s talk about a couple of points that you raised. I want to talk a little bit about costs, right? So, you’ve raised the question of costs in terms of having unanticipated consequences for people, particularly at the lower end, so that’s a type of cost. You were also talking about costs, but you’re talking more about monetary costs.

Veronique de Rugy: Not necessarily, I was talking, I mean, I was talking about both. I mean the budgetary aspect is definitely one of those, but we can decide as a society if what is discussed is worth it. The problem is, like, that I think not without thinking about it seriously, should we agree to actually set ourselves up with so much you know, new spending? But also, I mean, I think the one that’s like the most problematic cost, at least this one’s visible, is actually the cost that most people don’t see, which is lower employment, possible discrimination against women, lower wages, lesser chances of advancement, and these are not very visible costs.

Rachel Greszler: Well, and I worry with those that they tend to affect the lower-income earners the most, or people who have just started out in the labor market, who are more likely to have a child and take that longer leave. And so, you put mandates on those, and then you’re gonna end up having more discrimination. And whenever something becomes an entitlement, or a mandate, instead of just worked out independently as needed, people tend to take more of it. People have assumptions about somebody, whether they’re going to take it or whether they’re not, and you just have these consequences that aren’t really worth the cost of what it was to begin with. And my fear is that when it becomes a government program, they tend to grow over time. You know, we have Social Security. It was only supposed to take 2% of our paychecks, and now it’s 12.4%, and it’s rising to over 17% without doing something to change the program. And the same has been the case in countries across the world that have paid family leave programs. They start really small, and they’re trying to meet more needs. That’s why they’re expanding, because they aren’t able to get everybody’s needs. And so, they increase the eligibility, the amount of time they can take, the amount of pay they receive, to try and get everybody into them. But then those costs really explode.

Camille Busette: You know, what, in the end, are we really solving for, right? So, what is – you know, when we think about paid family leave, what constitutes a success around paid family leave? So, from my perspective, for the U.S., what we’re trying to solve for is a vibrant economy, moving into, you know, well into the 21st century, where we are making sure that the healthcare costs that you know, currently exist, which are projected to go up to about 19% of our GDP by 2027, that where those are relatively contained, in a sense that the rate of increase is not above what we can manage. And so, I think we really need to think about the bigger picture. So for me, paid family leave is in a larger context, which is, how do we get, make sure that we maintain economic growth? And one important way of doing that is to make sure that you have increased labor participation. And, as we know, women are increasingly a larger share of that labor participation pie. We want to make sure that that is increased over time, and so paid family leave is one way of doing that. Remember, when we have lower labor participation rates, we have less money circulating, and less money circulating in a consumer-driven economy is one that is poised for lower growth.

Rachel Greszler: That’s one point that I would disagree on, because I feel like the role of the government is not to push people into one area or another. It’s not to tell a parent that they should stay at home full time, or that they should work full time, or do a combination of the both. It’s not to say that you should go and take care of your mother, your elderly father, but to give them the resources to be able to make the choices that they need to, because the difficulty is if we do that and we say this is what society deems is valuable, staying home with your children for the first 12 weeks, being able to take up to 12 weeks to care for a family member, and maybe, you know, in some states it’s a close friend. There’s all different definitions. We have to define it. And you have to put a box around who qualifies, how much leave are you allowed to take, and then that box has to get so broad that the costs becomes so expensive that you’re really burdening everybody and particularly the lower-income people. I mean, I just imagine the government program and as all these applications are coming in and they’re determining: Does this leave qualify? Does this one not? How close are they really? They say they’re like a family member, but are they really? That’s the type of interaction that I don’t see a government agency and bureaucrats sitting there being able to meet the needs. And when we look at paid family leave, most of us think about okay, the birth or adoption of a child. We all want parents to be able to stay home with their children. That’s actually only one out of every five leaves in the U.S. that are taken. And a lot of those other leaves are intermittent, there are emergency-type situations where you have to walk out that day or the next day. In these government programs, they would have at least, you know, a week waiting period after the application has been received, after the doctors’ notices have been filled out. And the reality is, that that’s not going to benefit a lot of people and it’s particularly not gonna benefit the low-income workers who can’t go for two weeks or maybe two months before that check starts coming in from the government. And so, they might not end up using the benefits. And you’re gonna lose, instead, the benefits that are already there in the private sector and that we’re seeing expand over time. Because, the reality is, everybody wants access to paid family leave.

Caleb O. Brown: To both you, Rachel, and you, Veronique: If you’re not broadly supportive of the idea of a mandate for paid family leave, what are the interventions that are current in the labor market that make it more difficult for employers to offer that?

Rachel Greszler: In general, it’s taxes and regulations. And I think that’s why we’ve seen over the recent years, both because of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act and some lower regulatory barriers, that we’ve seen significant wage growth, and it’s been most pronounced for the lowest income workers. They’ve had twice the wage gains of the highest income workers. There are other things that are out there. There are barriers such as, we don’t allow private sector workers or employers to have the choice to earn what we call so-called comp time. State and local workers can do this. If they work overtime for two hours, then they can have three hours of paid time off. But we prohibit that in the private sector. Something called the Working Families Flexibility Act would just make that something that employers are allowed to offer to them. And there’s also some barriers just in terms of families not saving enough, because we have these targeted savings accounts. You can save for college, or retirement, or health care, but we don’t have a general account. And so, if you had something like a universal savings account, USA accounts, you could tap that for whatever the need is, whether it’s paid family leave, or childcare, or college. Just making it more available to families.

Camille Busette: Let’s talk a little about low-income workers. So, I think we’re all agreed, they don’t really participate in whatever is offered, whether it be particularly at the – from private companies. So, to me, that does represent a market failure. And so, the question is, if we definitely see that those, those workers are not participating and they’re not benefiting from a range of options that are out there, then what is the solution?

Veronique de Rugy: I would phrase it completely differently, which is, it’s not that there’s a market failure, it’s when you actually look at the reason why they don’t have it, it makes sense. Usually, the employers are really small, they’re temp workers, they’re hourly workers. But more importantly, I think this notion that it would cost them nothing is actually wrong. Because while their total competition may actually, may be increased in a time one, it will be over time at the expense of wage, of their actual money that they put in their pocket. And that, to me, is another reason why it explains why those workers don’t particularly have it. It is because when you top, when you put on a benefit on top, ultimately what you’re saying, you’re saying that every one of these workers would prefer having the benefits than having the cash. And that…

Camille Busette: So, this is, this to me is, this to me is where it’s important to talk about what we mean by a mandate, right? So, there are mandates that can cover everything, the type of leave, the amount of time, the percentage of salary that’s covered. Right? So that’s your typical formula, and that could extend across the U.S. on a federal basis. Right? So that’s one type. Then we have state leave. Then we could have federal mandated leave that talks if you if your salary is above – below a certain level, so threshold-based mandates. So, that’s one way of thinking about how do we get at the fact that lower-income workers are nearly not participating in this? And I’m just going to say from my perspective, that I think it’s really hard for us, to make us here, you know, with the kind of jobs we have, to sort of make a – to make a conclusion about what it is that lower-income workers would want, whether they will want wages, you know, more time off, et cetera. So, they need to have options, right? And if it’s not happening in the market, a complete classic definition of market failure, there’s demand, and it’s not happening in the market. That’s not happening in the market. Are there not ways in which we can craft federal mandates that address specifically these low-income workers?

Rachel Greszler: Can I challenge the definition of market failure here and whether that applies? Because in a lot of the cases you look at countries that have the programs. They have widespread access and availability, and even some of the states and cities in the U.S., they have instituted benefits. San Francisco, 100% benefits to mothers, and yet low-income mothers were half as likely to use that program as the higher-income mothers. When it’s the choice of the individual, it’s not a market failure. It’s provided, it’s accessible, and yet certain individuals are less likely to choose to use that program. And those are things that I don’t think that we can mandate and force a family to say you need to take time off to care for this family member or to care for this child if that’s not the choice that they’ve decided is best for their family.

Camille Busette: But that’s not what we’re talking about in terms of mandating. We’re talking about having the option, right? So, employers of those low-income people, you know, temporary workers, itinerant workers, et cetera, employers have the mandate. It’s not the actual caregiver. So, in the case of San Francisco, which is, of course, a very progressive city and has instituted something like that, what happens there in San Francisco is what you’ve seen is that people are exercising choice, but they have a choice. So, the sort of, the analog would be having a federal mandate on employers across the U.S., who are, you know, where they have workers who are making less than a certain amount, and then seeing if the results would be somewhat similar, which would probably be the case. Some would take it up and some wouldn’t, just as you see at higher-income brackets as well.

Veronique de Rugy: But the problem is that once you mandate it, once you mandate it, no matter how good the intentions are, and even if you say employees can take it or not, the problem is that employers may actually start discriminating against those they assume will take the benefit. It is clear that it actually does have a cost for women and low-income women in particular, and so, in terms of lower wages, lower promotion, some discrimination against women and that is a cost that is very hard for me to support for women who are already struggling because their low wages.

Camille Busette: Well and I agree with that, but in all those countries that you mentioned, and particularly in this country, I mean, women face much greater barriers to employment and advancement than men do, just generally. It’s in the water. So, the way to manage that, we are all policy professionals, the way to manage that is when you mandate family leave at whatever level you’re mandating it, you make sure you attach riders that link into our legal infrastructure and make sure that those protections exist legally. That doesn’t mean that every employer is gonna follow it, but at least the employee will now have legal recourse to make sure that he or she is treated properly.

Caleb O. Brown: All right, we’re gonna take a question from our audience.

Audience Member 1: My question is how would paid parental leave affect people’s decision-making? And how would it impact U.S. demographics?

Rachel Greszler: I’d be happy to start with that. You know, knowing that you have the option to take time off and for it to be paid, particularly if it were 100% pay, that would make a difference. I think that some people would be certainly happy to have that and might start having children a little sooner than they otherwise would, but the reality is I don’t think it’s going to make a big difference in people’s decisions because the first 12 weeks of having a child are only the start. You know, childcare is extremely expensive. There’s 18 years ahead when you have costs that are associated with raising children. And really addressing just those first 12 weeks I don’t think is going to make enough of a difference to change somebody’s mind between having a child, or another child, or not.

Camille Busette: There is actually an interesting study that was done last year in Spain actually comparing couples that had taken family leave before a 2007 law that allowed men to take parental leave in Spain. And one of the things that they found was that in the families where the man now took parental leave, there was a 7 to 15% chance that they probably wouldn’t have a second child. And they ascribed that to the fact that now the dads are like, wow, you know, spending time…

Veronique de Rugy: It’s a lot of work.

Camille Busette: …with very young kids, with infants, is time-consuming and, you know, labor-intensive.

Veronique de Rugy: It is really kind of interesting to actually think that one of the things that paid leave does, in many of these countries that have been studied, is that they actually, people revert even more to their gender role. So, there are – women tend to take more leave and to be more the ones who take care of the kids, even in countries where they have very gender-neutral family benefits.

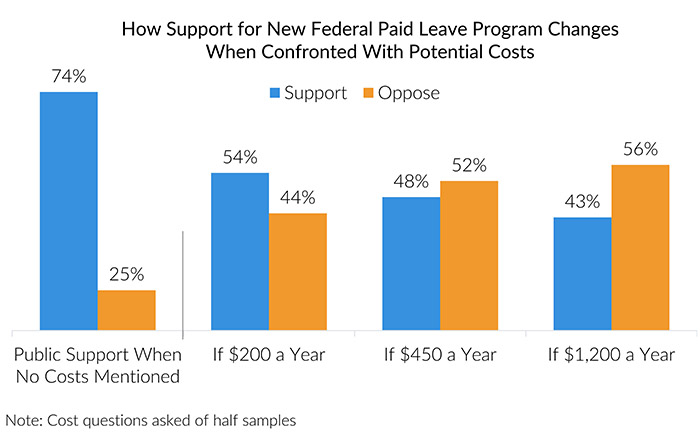

Rachel Greszler: Yeah. I think a broader question here is what helps working families the most? How can you balance work and family? And Cato polled, surveyed, you know, and they asked, they gave six choices. And 60% of respondents chose two of the answers, which were a more flexible work schedule and the ability to work remotely. And so there, those are the flexibility options. Only 6% of people chose more paid parental leave, and so I think that we want to help working families in whatever way that they need it, but let’s look at the biggest priorities that they have.

Caleb O. Brown: All right, we’re gonna take another question from our audience.

Audience Member 2: Should there be any special considerations for small businesses as they implement paid leave programs?

Camille Busette: So, I’ll take that. I think absolutely small businesses are very different from larger multinational corporations. I think the way you manage that is you have a tax credit, or something like that, that can incentivize them.

Rachel Greszler: Yeah, but that – this does bring up the issue of the consequences of paid family leave that are not like the discrimination or the wage impacts. And they’re not the direct monetary costs, but just the ability of that business to still function without having that worker there. And so, this is not just whether it’s paid leave, but also just the ability for workers to take time off and have job protection. You know, we all want them to be able to do that, but we do have to recognize the reality that when a worker is gone, it’s hard for that business to keep running.

Camille Busette: No, I agree that’s an important consideration. But I think it’s also incumbent upon the business to plan ahead.

Veronique de Rugy: But the truth of the matter is like, over time, depending on the cost and the burn for that company, whether we want it or not. It is true that if you go from five to four employees or five to even three, right, I mean, it is not surprising that over time, some employers are going to be deciding not to use women. And that’s – this is why ultimately it is always better to have employee, employer, employees, try to, you know, figure it out themselves. And I agree that what we would want in that relationship is something that is where it’s a level playing field between the two, and, but I think we just can’t – of course we would all want, you know, more for low-income Americans, but we really have to be careful that the benefits doesn’t backfire and hurt them even more.

Camille Busette: So, I just want to address that. You know, I do think it’s important for us to think about smaller businesses very differently. And yes, it’s very possible that smaller businesses may gravitate in a sort of, in a constant, in a context where there are no legal protections would gravitate to hiring, you know, people who are not gonna take paid family leave, but the reality is that we can’t have paid family leave trying to solve every single problem. Paid family leave is in a context. It’s in a legal context. And if we think that that’s a problem, we strengthen the legal provisions around discrimination in employment or we utilize the ones we have that exist currently and may be underutilized.

Caleb O. Brown: We have another question.

Audience Member 3: What are some alternatives to paid family leave for low-income parents?

Rachel Greszler: One of the policies that I talked about earlier is called the Working Families Flexibility Act. And so, this would just allow those lower-income workers, it only applies to them making about $35,000 a year or less, and they could accumulate paid time off at a rate of 1.5 hours per hour of overtime work. And so, somebody who just works a couple extra hours a week would be able to accumulate, you know, three to five weeks of paid time off per year. And so, that’s one thing that I like that would particularly get at that lower-income group.

Camille Busette: But I think the question is talking about currently, and currently it’s – status quo is exactly what we’ve been describing during this conversation, which is not, not too many other alternatives.

Rachel Greszler: No, but we are seeing, you know, the more that wages grow, and the more resources that employers have, that’s where we’re seeing more of them offering policies. And we’re seeing individual families have more money that they are able to take off, even if it’s two days or one week. They’re not all 12-week leaves, but they’re having that ability to take some unpaid time off.

Veronique de Rugy: And by the way, this is why universal savings accounts would be actually great, because, as we’ve said, the paid parental leave is only one, is one of the many needs that parents have to leave work. And so, it would be great when people can save more but don’t know when they’re going to be able to use it, to put this money in a bank account and be able to take it out no matter what. Because the truth is, we all have children. I mean, there are things that happen where you have to go, and you haven’t planned for it, and you don’t know. So, increasing flexibility for the savings for the relationship with employers would be great.

Caleb O. Brown: We’re gonna go to closing statements, and just, what are your big takeaways from this conversation, and what do you want people to take away from what you said today? Vera will start with you.

Veronique de Rugy: So, I think we all agree that there a lot of benefits to paid leave. We also agree that the Americans who don’t have paid leave, contrary to the rhetoric, as if people are talking about, as if there’s no paid leave program in the U.S., are low-income earners, and they are the ones who we would like to help. But what I would like people to think about and take away from this conversation is, benefits – highlighting the benefits of the program is one thing, we need to highlight the cost, and these costs are not just budgetary costs. They are also costs in terms of lower wages, possible discrimination, a lower promotion rate. And I think this is important because, I actually, unfortunately, I think that with this particular issue there is no silver bullet. Every policy that we will put in place will have costs that people who are benefiting them may actually come to regret or may not actually realize that they’re really suffering from it, to sum it up.

Camille Busette: So, you know, I think this has been a great discussion and I think, you know, paid family leave is an important tool that should be part of a larger policy kit where we really message and put into practice some opportunities for American families to really be families and to be able to pursue what that means for them. Paid family leave is part of that. And I certainly think, and I agree with you that, you know, at the lower end we’re not seeing the kind of benefits that we really need to see, and so, for that reason, I think we should very seriously be considering how the federal government fits into that picture, particularly when we’re thinking about lower-income families.

Rachel Greszler: Yeah, and I’ll pick up on that. You know, agreeing that where we want to go is to help those who don’t have the access to the leave today, and we know that that’s lower income and smaller employers. And I would just like to have a caution that we need to look at these policies holistically and think through, will it actually help the people we are trying to help and is this the best way for the individuals to get access to this? And everything that I’ve looked at across countries and states has said that you actually end up not benefiting, you know, half the people that need the leave and you’re regressively hurting the lower-income families at the expense of benefiting the middle and upper-income ones. And when I see that evidence, I turn towards solutions of what families say they want to help balance work and family life, and that is more flexibility instead of just a government program that specifies those benefits.

Caleb O. Brown: Thank you for joining us for this episode of Sphere, and you can find more episodes at ProjectSphere.org, and we’ll talk to you again next time.